The “Antiracist” Mental Health Threat that No One Talks About

By Stanley K. Ridgley

ACADEMIC QUESTIONS, Spring 2022

“Antiracist pedagogy” is a major element of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion ideology that has found a comfortable home in the American university.

But antiracist pedagogy is much more than an abstract self-evident term designed to elicit unqualified support. It has a particular meaning, content, and method, and its details are available to anyone who digs into the literature published in esoteric journals of university schools of education and off-campus non-profits.

Save for a handful of remarkable investigators and journalists, however—Christopher Rufo of the Manhattan Institute gets honorable mention—not enough people do the digging, so here’s the key: Antiracist pedagogy is a psychotherapeutic intervention program that divides students into two arbitrary categories based on race and dictated by ideology—oppressors and oppressed.

The content of antiracism consists of a mélange of pseudoscientific speculations informed by paranoia that are then codified into a provincial theory emerging from schools of education.1 It is unsound and has no foundation in legitimate social scientific circles.2

Antiracism is typically delivered in a program of coercive thought reform that deploys psychological weapons against undergraduate students. The centerpiece of this crude coercive method is an explicit attack on “central elements of self,” a key marker for what psychologists have characterized as second-generation thought reform programs that “neutralize a person’s psychological defenses.”3

In this respect, antiracist pedagogy is not pedagogy in the conventional sense. It is actually a form of crude psychotherapy, cobbled together from various hip-pocket smatterings from the literature of psychology.

Techniques used in clinical psychotherapeutic practice are often appropriated into antiracism programs. Hence, much of what has been learned about the management of emotional experience in the practice of clinical psychology and psychiatry is brought into play as a method through which the target is made to experience intense emotion.4

During these therapy sessions, delivered either by classroom faculty or workshop student affairs amateurs, undergraduates are urged to make themselves vulnerable in a “trusting” environment. Facilitators wheedle students to reveal private information about family life, personal beliefs, sexual identity and such, perhaps by writing in journals or verbally in “twelve-step” fashion.

The student’s private revelations are filtered through the racialist interpretation and then turned back against the student at his most vulnerable points.

Antiracist pedagogy attacks white students as victimizers and for their “complicity” in a system fabricated by antiracist ideology; it attacks students of color as psychologically deficient if they do not accept their scripted role as victims.

These psychotherapeutic programs are generally “facilitated” by faculty or staff, who are often uncredentialled in the field of psychology. They typically do not offer students an informed consent narrative to explain that they will be participating in a behavior modification “stages of development” program; neither are students told the risks of the intervention, which is rarely vetted by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the psychological impacts involved.

Folks running these campus programs are cavalier about the psychological abuse these assaultive programs inflict on students. They scoff and assert that negative student reaction is mere “discomfort” or “resistance” or “bad attitude.”5 Nor are the faux pedagogues interested in counterargument.6

Sound bad? It gets worse.

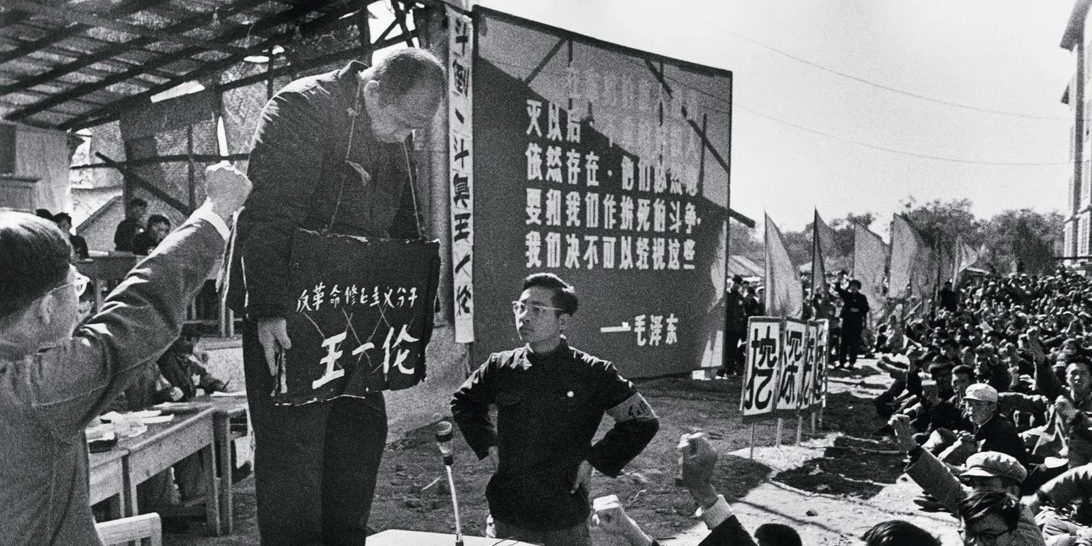

This antiracist pedagogy constitutes a renegade program emerging from one of the least academically rigorous units on campus—schools of education. These schools were long ago colonized by neo-Marxist and Maoist critical pedagogy and enraptured by the work of Paulo Freire, a Brazilian Maoist and education school patron saint. As a result, antiracist pedagogy mimics the thought reform program developed by the Chinese during the Maoist period and endorsed by Freire, who called Mao’s murderous Cultural Revolution the “most genial solution of the century.”7 Additionally, it explicitly incorporates the early psychotherapy behavior modification work of Kurt Lewin.

If this weren’t enough, antiracist pedagogy employs techniques refined and utilized by contemporary cult groups to seduce recruits through taking advantage of their vulnerabilities. In her exposé on the Unification Church, Eileen Barker detailed the multiple techniques used by the church to attract and deceive recruits. Her chapter titled “Environmental Control, Deception, and ‘Love Bombing’” describes how the church enthusiastically envelopes recruits with unqualified acceptance in order to retrieve personal information that is later leveraged to strengthen church control. This is eerily similar to the first stage of workshop methodologies employed on campus, as one of the early antiracism texts indicates.8

[I]f the environment is perceived as supportive, a person’s defenses can be more permeable. . . . Our goals in this phase are to create an environment in which students feel confirmed and validated as persons even as they experience challenges to their belief system.9

The reality is that unsuspecting undergraduates are subjected to psychotherapeutic behavior modification techniques without their consent and without the risks explained to them. For persons with any pre-existing mental fragility, this could be disastrous.

This type of programming inflicts intended psychological stress and can cause psychological damage that is identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013) as a type of “dissociative disorder”: “Individuals who have been subjected to intense coercive persuasion . . . may present with prolonged changes in, or conscious questioning of their identity.”10 The manual lists “brainwashing” and “thought reform” as causes, and it identifies additional symptoms that programs can generate, such as “discontinuities in sense of self and agency or alterations of identity.”

Moreover, the psychological damage inflicted is precisely the kind of stress that can enhance the incidence of college student suicide. One university psychologist has explained that feelings of guilt, hopelessness, and worthlessness are associated both with suicidal thought and action. The unsparing guilt-inducement promoted by Critical Race Theory, the underlying system of thought behind antiracism pedagogy, as well as its attacks on students’ sources of identity and self-worth, could push vulnerable people not merely to the point of despair and self-loathing, but to acts of self-destruction. This is a time when many universities are grappling with serious mental health problems on campus.11

In these parlous times, if you ask yourself, who in his right mind would do such a thing as attack an undergraduate’s “sense of self” or try to “deconstruct” a student’s relationship with his parents, you need look only to the practitioners of “antiracism.” University of Iowa education professor Sherry K. Watt developed a psych-conversion program based on Anna Freud’s 1937 work that does just that.

Watt’s program is called the Privileged Identity Exploration model, and it attacks and intentionally destabilizes the student’s “sense of self” and can “necessitate” the deconstruction of student familial relationships and friendships.12 This is how cults alienate vulnerable young people from family.

Watt is no fly-by-night diversity consultant. She is a full professor at the University of Iowa and an influential “senior scholar” of the American College Personnel Association (ACPA), a national organization that sets standards for student affairs graduate programs in schools of education.

Watts’s program is not the only one that seeks to inflict psychological trauma on students, or as antiracist pedagogues call it, “discomfort.” The idea is to unfreeze the student’s belief system and replace it with one provided by the practitioner. These techniques usually contain some aspect of moving the student along a psychological conveyer belt of behavior modification—this is a typical theme in the work of Janet Helms, Beverly Daniel Tatum, Ricardo Gonsalves, and others who adopt a psychological stages model of behavior modification.13 It is also the explicit method of thought reformers and cults.

The coercive thought reform program combined with amateur psychotherapy interventions is standard fare for much of what passes for pedagogy in the antiracist curriculum and in the so-called co-curriculum. This co-curriculum is where amateurs with online master’s degrees in “counseling” run “difficult dialogues” and “courageous conversations” and “racial caucuses” and “Brave Spaces.” These are all variations of the same tainted antiracist intervention, the same ideological content, the same amateur psychotherapy, the same coercion to break down “resistance.”

But the public face of antiracist pedagogy is quite different from many of the egregious interventions actually implemented. The antiracists’ public messaging masks the overt psychotherapeutic elements under a benign rubric of “student learning” or “learning about race.”

When pressed to reveal their content and techniques, antiracist pedagogues typically offer tepid, even wholesome examples of a faux antiracist pedagogy. Perhaps they mention “implicit bias” in a kind of Potemkin village deflection, or they talk about avoiding standard stereotypes in the classroom, or they share collections of anecdotes about “power and privilege.”

But much of the closed-door content is toxic and offered up by self-styled racialist gunslingers. One of these is Emory University professor of philosophy George Yancy.

Yancy, a critical racialist, is skilled and experienced in his attacks on his students. He acknowledges that under his bullying, “White students often persist in their denials, they shift in their seats, their faces contort in great discomfort . . . some have teared up.”14 He continues, not a scintilla of doubt to disturb his certitude: “[I] hope to change my white students’ understanding of racism so they can begin to see themselves as racist.” Ricky Lee Allen is a racialist associate professor based in the school of education at the University of New Mexico, who intones that “critical educators need to create an environment of dissonance that brings white students to a point of identity crisis.”15 These two amateur racial psychotherapists at least get kudos for candor if not good sense.

The reality is that university-sanctioned antiracist pedagogy and programming creates a wholly contrived hostile mental health climate on campus, especially for undergraduates and first-year students.

The vulnerability of first-year students has long been recognized as an opportunity for “early intervention.” This makes freshmen orientation—a time in which new students are more likely to listen because they are anxious, frightened, or eager—a special time for antiracist intervention.16 As such, this type of programming has the potential to take vulnerable younger students down a grim path, especially students who are already afflicted with risk factors such as depression, anxiety disorders, social alienation, loneliness, and family instability, among other indicators.17 It also increases liability for any university that condones these clumsy psychological interventions. Even in classes whose content is not explicitly informed by racialism, antiracist pedagogues apparently accept no limits to their psychological assaults on students, even against those who have been identified as “neurodiverse.”

One racialist faculty member at a business school in Alabama openly mocked a mentally disturbed student, who had never expressed any sort of racial animus. The instructor, Paula R. Buchanan, took great pleasure in the abuse as the student’s face turned “beet red with shock and embarrassment.”18 Ms. Buchanan’s master’s in public health from Tulane University and her certification in public health from the National Board of Public Health Examiners gave her no pause. In fact, she recounted this grotesque tale of bullying as a heroic “victory.” “Internally, I giggled with glee at what I had done,” said Buchanan.19 This is the dark reality of antiracist pedagogy in its extreme practice.

This reality suggests to us what should be done about it. And about the people who practice it. University legal departments are usually fastidious in assessing college liability for malfeasance that can lead to lawsuits and large payouts; they should advise university presidents to pause these “antiracist” programs immediately. Before any kind of antiracist program is reinstated, actions that enhance transparency should be taken. These actions should include 1. An evaluation of the content and method of these campus programs by an authority outside of racialist circles; 2. polling students about their experiences in these programs and all results made public; 3. vetting the credentials of those administering antiracist amateur psychotherapy sessions, by a psychology authority outside of racialist circles; 4. making public all details of the program procedures to university stakeholders; 5. ensuring that if such programs are reinstated, future participants receive explanation of the risks and provided with the appropriate informed consent forms; and 6. potential student subjects in antiracist sessions should be screened for risk factors prior to participation.

As it stands now, there is little to no oversight or even public awareness of these activities, but it is imperative that any psychological trauma caused by the coercive psychological attacks on students in antiracist programs be identified and made public. These likely include the destabilizing of the sense of self, destabilization of relations with family and friends, alienation, depression, and even suicide.

These questions must be asked and answered now before a student is pushed to the psychological brink by an antiracist pedagogue who “giggles with glee” while “doing the work.” In such a case, it will not go well for the school or for the persons practicing this amateur psychotherapy.

1 Peter Trower and Paul Chadwick, “Pathways to Defense of the Self: A Theory of Two Types of Paranoia,” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2, no. 3 (Fall 1995): 265; Theodore Millon, Modern Psychopathology (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, 1969), 328-329.

2 Antiracist Pedagogy is a major theme in education schools and in several cultish “education” journals. Emblematic pieces from this literature include Kyoko Kishimoto, “Anti-racist pedagogy: from faculty’s self-reflection to organizing within and beyond the classroom,” Race, Ethnicity and Education 21, no. 4, 2018: 540-554; Jason Arday, “Dismantling power and privilege through reflexivity: negotiating normative Whiteness, the Eurocentric curriculum and racial micro-aggressions within the Academy,” Whiteness and Education 3, no. 2, 2018:141-161.

3 Richard Ofshe, Margaret T. Singers, “Attacks on Peripheral versus Central Elements of Self and the Impact of Thought Reforming Techniques,” Cultic Studies Journal 3, no. 1 (1986).

4 Ofshe, Singer, “Attacks on Peripheral versus Central Elements of Self.”

5 Kari B. Taylor, Amanda R. Baker, “Examining the Role of Discomfort in Collegiate Learning and Development,” Journal of College Student Development 60, no. 2, (Mar-Apr 2019): 173-188.

6 Robin DiAngelo, Ozlem Sensoy, “‘We don’t want your opinion,’: Knowledge Construction and the Discourse of Opinion in the Equity Classroom,” Equity and Excellence in Education 42, no. 4, 2009.

7 Paulo Freire, “Conscientisation,” CrossCurrents 24, no. 1 (Spring 1974): 28.

8 Eileen Barker, The Making of a Moonie: Brainwashing or Choice? (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984), 173-188.

9 Lee Anne Bell and Pat Griffin in their “Designing Social Justice Education Courses,” in Maurianne Adams, Lee Anne Bell, and Pat Griffin, eds., Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (New York: Routledge, 1997, 2007, 2016), 73.

10 DSM-5: 300.15 (F44.89).

11 Natalia Mayorga, “UNC-Chapel Hill in a ‘Mental Health Crisis,’” The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, November 8, 2021.

12 Sherry K. Watt, “Moving Beyond the Talk: from Difficult Dialogue to Action,” in Jan Arminio, Vasti Torres, Raechele L. Pope, eds., Why Aren’t We There Yet?: Taking Personal Responsibility for Creating an Inclusive Campus (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2012), 135; Sherry K. Watt, “Difficult Dialogues, Privilege and Social Justice: Uses of the Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) Model in Student Affairs Practice,” The College Student Affairs Journal 26, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 118; Sherry K. Watt, “Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) Model Revisited,” in Sherry K. Watt, ed., Designing Transformative Multicultural Initiatives (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2015).

13 Janet Helms, “Toward a Model of White Racial Identity Development,” in Janet Helms, ed, Black and White Racial Identity (Westport: Praeger, 1990); Beverly Daniel Tatum, Why are all the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? (New York: Basic Books, 2017); Ricardo Gonsalves, “Hysterical Blindness and the Ideology of Denial: Preservice Teachers’ Resistance to Multicultural Education,” in Ideologies in Education, Unmasking the Trap of Teacher Neutrality (Peter Lang, 2007): 3-27.

14 George Yancy, “Guidelines for Whites Teaching About Whiteness,” in Stephen D. Brookfield & Associates, Teaching Race: How to Help Students Unmask and Challenge Racism (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2019), 29.

15 Ricky Lee Allen, “Whiteness and Critical Pedagogy,” Educational Philosophy and Theory 36, no. 2 (2004): 133.

16 Arthur Levine, “Guerilla Education in Residential Life,” in Charles C. Schroeder, Phyllis Mable, and Associates, Realizing the Educational Potential of Residence Halls (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994), 102.

17 “Risk Factors,” Suicide Among College and University Students in the United States (Suicide Prevention Resource Center: May 2014), 2-3.

18 Paula R. Buchanan, “The Convenient, Invisible, Token-Diversity Hire: A Black Woman’s Experience in Academia,” in Nicholas D. Hartlep, Daisy Ball, Racial Battle Fatigue in Faculty (New York: Routledge, 2020), 185.

19 Buchanan, 185.

CLICK HERE to Read at Academic Questions. . .